CSU.TO: Constellation Software (2)

Preface

Refer to these articles for:

This post will focus on some risks we can think of investing in CSU. By breaking down the risks, this exercise serves to explain our conviction through elimination.

Risk #1: Copying CSU Playbook

The only barrier to starting a software conglomerate is a phone and a cheque book.

Mark Leonard, founder & Chairman of CSU

On paper it may sound deceptively easy to compete against CSU, but in practice it’s very challenging. There are certainly competitors (eg. Halma, Addtech, Danaher, Visma…) who copy CSU playbook, however they don’t grow to the size of CSU.

Why so?

First Mover Advantage

CSU was the first of its kind to write the playbook of acquiring VMS companies. Being a first mover, it has built up reputation and relationships over decades. The “phone book” Mark Leonard mentioned is actually quite extensive and hard to get your hands on.

CSU tracks every target it had a conversation with and all that data goes into an internal database which senior leaders have access to. No doubt there has been a proliferation of copycats in the recent years, particularly in Europe. Typically how they start is grouping up a few people who have some adjacent industry knowledge and then raise money, after that they go and buy companies. The challenges competing against CSU are:

There is a buying process when acquiring a target. CSU has the capital, human resource, knowledge base, long-term reputation. What advantage does the copycat have?

These VMS companies are usually led by founders. Suppose that the selling price is the same, and founders care about the legacy of their company, CSU is the proven acquirer. Why would they choose a copycat?

The copycat will need to offer a high price to get the sales, and that’s not an advantageous thing to do.

There are indeed some acquirers (eg. OpenText) that have found success by focusing on small niches. CSU is pretty much in most of the verticals globally.

Reputation

CSU is a long-term holder of VMS companies, on record they have only sold one company in the early days because they paid too much for it. CSU is top of the list for any seller who cares about their company. For those who care more about the price, CSU wouldn’t be interested. This self-selection mechanism ensures that CSU acquires good operating managers who are in for the long-term.

Operating Post-acquisition

CSU has built an ecosystem and knowledge base which allows acquired businesses to operate successfully. They target matured businesses which are well-run, ideally still led by the founder. To incentivize the owners to continue operating, incentives are set to earn-out over a few years. Usually, these owners stay beyond the earn-out period, about 70% of senior management were former entrepreneurs who sold to CSU in the past.

What you get is a network of experts from all sorts of verticals. This human resource is a huge advantage against new entrants.

If a manager departs after acquisition, CSU has a deep bench of talent that can replace and continue operations.

Opportunistic Buyer

For small VMS companies led by entrepreneurs, the journey to selling their company is a very personal thing. That’s why CSU tracks conversations of all their potential leads. At any given year there will be someone who wants to sell their business for whatever reason.

It could be a few years between conversations until a founder decides to sell. To compete against CSU web of relationships is very difficult especially if a new entrant just entered the market.

Risk #2: Return on Investment

CSU adopts a tiered hurdle rate:

30% for smaller deals (<$1m revenue)

25% for mid-size

20% for larger deals (>$4m revenue)

Potentially lower rates (15%) for very large transactions (>$100m revenue)

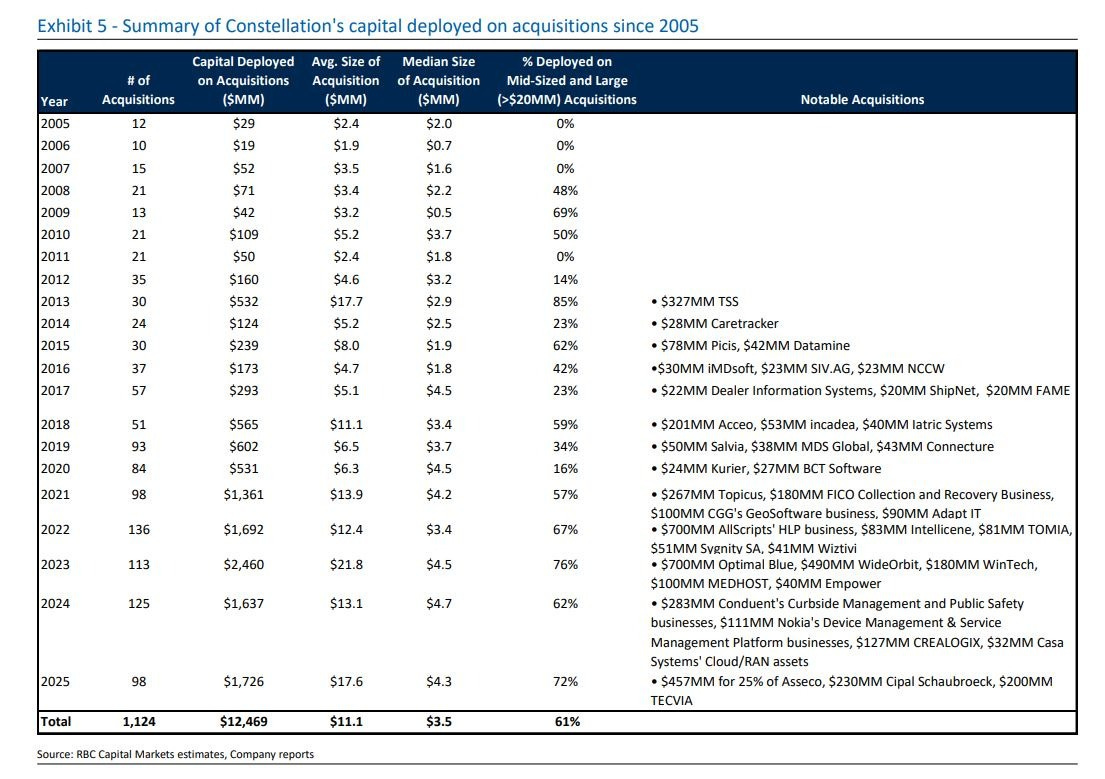

To move the needle at CSU, it needs increasing deal size, which inevitably lowers ROIC. However, the median size is still quite small compared to the average, meaning that only a few large acquisitions happened while the rest are still very small. If the median is $4.3m (2025) and CSU pays average 1.5x P/S, then the typical small company does under $3m revenues (although CSU calls this “mid-size”).

Why has competition not been able to drive up prices since it’s known that CSU hurdle rates are too high?

In other words, how defensible is their ROIC?

Yes, sales multiples have indeed moved up as competitors like private equity firms are willing to pay more. However, private markets function differently from public markets.

In public markets you can get silly prices, companies are driven by what multiples their peers are selling at. Private markets are much more rational, you are negotiating with a single seller who knows his business deeply. They will not offer an irrational price.

Competitors will therefore also not buy at irrational prices. Disciplined buying/selling is more prevalent in private than public markets.

We see some public markets action in 2025, through its subsidiary Topicus, they acquired a minority stake (24.84%) in publicly traded company Asseco Poland. This was the first time CSU deployed capital in public markets.

We can look at this in 2 ways:

Opportunities in private markets are drying up as CSU grows in size.

CSU doesn’t care as long as ROIC is good.

The worry is that CSU is willing to accept a lower hurdle rate because public purchases are easier to execute.

On the other hand, the spin-outs of Topicus & Lumine also benefits CSU in terms of multiples expansion after they float on the public market.

There are concerns that the VMS market terminal value is zero, this is not new and Mark Leonard himself has wrote about it in 2017:

If Constellation had started in 1895 instead of 1995, we might have had the objective of being a great perpetual owner of daily newspapers. The newspaper industry underwent a long period of high growth which attracted many new entrants, followed by local consolidation, conglomeration, and eventual decline. I anticipate that the VMS industry will evolve similarly.

Despite saying this, CSU capital deployed increased by 5.9x since 2017 while keeping the median acquisition size the same! Revenues went up by 4.1x and FCF grew 3.6x.

In fact, management is not rigidly tied to VMS only. Capital allocation skills are indeed applicable to a wide range of things, provided they develop the industry competency:

One day Constellation may find that VMS businesses are too expensive to rationally acquire. If that happens, I hope we'll have had the foresight and luck to find some other high ROE non-VMS businesses in which to invest at attractive prices. I am already casting about for such opportunities. If we don’t find attractive sectors in which to invest, then we’ll return our FCF to our investors.

Mark Leonard, 2017 letter

Quality of Acquisitions

We cannot check directly the quality of the businesses CSU buys. If they buy a low quality VMS, it won’t show up in the first few years, instead it reveals much later.

These are businesses with antiquated legacy software with a handful of customers, which is like buying an annuity stream that eventually dries up. The risk there is their organic growth rates are not great. If that turns negative at some point, it will be a challenge to manage.

As outsiders, we can only depend on the aggregate ROIC.

Risk #3: Organic Growth

We know that the VMS industry has low competition and the products are mission critical, so why is organic growth so low?

Where is the pricing power?

The profile of the end users are small/medium sized businesses. They don’t have big addressable markets to grow into, so the VMS companies likely have not reinvested into their software product to warrant price hikes.

Since the regular customers are small, when a bigger customer comes along, VMS companies are incentivized to give discounts to lock-in the business.

Niche VMS solutions have sticky relationships, even if there’s untapped pricing power, a VMS company might not want to immediately raise prices. This is especially true when they are long-term operators; longevity is more important to CSU.

CSU is unlike private equity firms. It doesn’t buy to sell at a higher exit price. So customer relationships are important, CSU has to understand everything about the needs and requirements of their customers before figuring out a buy price. Many factors go into a successful acquisition, pricing power might not be the main factor.

There are cases where pricing power is indeed weak, especially for legacy software that haven’t been updated and cannot justify price hikes.

Whether by design or strategic purpose, we think that CSU is not charging near their customers’ willingness-to-pay, implying latent pricing power (see here for discussion about pricing power).

If we look back into CSU history, Mark Leonard has tried several ways to improve organic growth. They ran experiments on increasing R&D hoping that it produces more organic growth, but the conclusion was that the money was better spent doing new acquisitions.

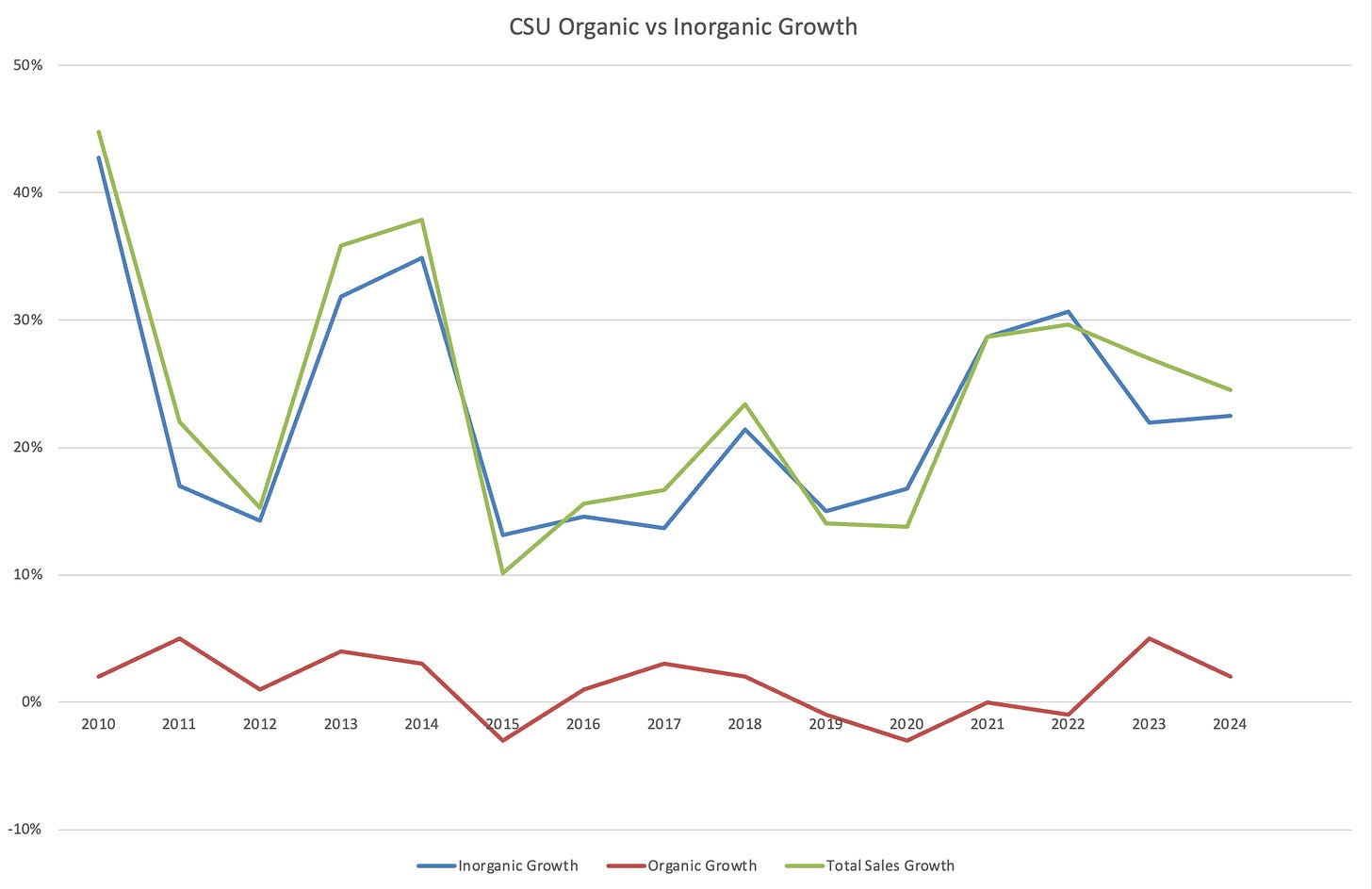

This led to CSU impressive growth being inorganic. It stems from the emphasis for employees to focus on acquisitions. The incentives & bonus structure is built around ROIC and capital deployment targets; it's very heavily skewed towards making good acquisitions.

Since CSU runs a “hold forever” philosophy, employees don’t have an exit multiple to benefit from. Hence, they are incentivized to think about cash flows and IRR. In an IRR calculation, cash flows in the early years carry heavy weightage. So if they were to focus on organic growth, it would typically require reinvestment into the business, and this will risk near term cash flows which reduces IRR.

As a result, managers will tend to acquire mature “cash cows” that produce predictable cash flows so that they can meet their hurdle rates.

The incentives structure explains why organic growth at CSU is difficult to ramp up.

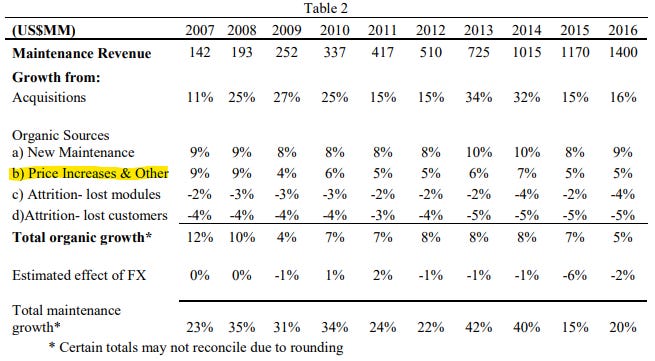

The last time CSU disclosed the impact of pricing was in 2016. We can see that pricing power is actually decently above average inflation of 1.8%:

Risk #4: Insiders Conflict

There is nothing to stop a CSU manager from taking his contacts outside and becoming a competitor (a few of them did). To counter this, senior managers are mandated to use 75% of their cash bonus to buy CSU stock at market prices. This results in top employees owning a significant sum of CSU stock which disincentivizes them to leave, especially when CSU has done so well.

On insider ownership: Executive officers are generally required to invest 75% of their after-tax incentive bonus into CSU shares (executive officers of Topicus buy subordinate voting shares of Topicus). The shares are held in escrow for a minimum average period of 4 years. Once in every 5-year period, executive officers may choose to receive their bonus entirely in cash.

For non-employee directors, they have to use all their director fees to buy shares on the public market.

Mark Leonard himself receives zero salary or bonus since 2015. His ownership of CSU is ~7%.

Since CSU stock has historically only went up, executives can feel reluctance when being forced to buy at expensive prices. We think the current drawdown of -45% presents a great opportunity for insiders to buy.

Due to this incentives arrangement, CSU has never issued a single stock based compensation nor repurchased any shares. Insiders purchased with out-of-pocket money at market prices. This is very rare in corporate America!

There is also a feature of inter-company competition. Although different Operating Groups cannot poach the same target unless there is no contact for 12 months, but in reality inter-company divisions are always competing and “trading” deals with each other. It’s best described by Rohan Noronha (head of M&A in Volaris group):

People always ask me who is your #1 competitor when doing these deals?

My answer has always been '“the other divisions”. Everyone is going after the same assets. Competition is extremely cut-throat from within.

It’s a source of frustration for many, but in the end it keeps people on their toes and engaged…

Risk #5: AI impact on VMS

In assessing targets, this is what CSU looks for:

Robust defensive moats, motivated teams, and operational complexities that reward experience and local knowledge.

Mark Leonard

The truth is nobody can predict what is the eventual impact for transformative technologies like AI. We are inclined to think that AI is beneficial to CSU.

Firstly, AI will improve productivity of the non-human work in the acquisition process. This is the most direct benefit, the ability to reduce analysis time and work through data. However, the human involvement cannot be replaced, relationships and trust are human factors. This fact doesn’t change: CSU will still be buying companies run by people.

Secondly, VMS is a tailor-made solution to specific problems. Imagine you operate a government funded K-12 education school (kindergarten), what do you spend most of your time on? Note: Harris School Solutions is one of CSU groups that supply VMS to K-12 schools.

Probably getting contracts, managing students, hiring teachers, planning school activities… you wouldn’t spend effort on IT as long as your software is functioning fine. Also, software expense is a small fraction of revenues.

Yes, you could hire someone to use AI, subscribe to a new AI cloud vendor, replace the existing solution… just to save an insignificant amount of cost while taking the risk of new IT vendor support and software incompatibility.

It doesn’t make economic sense.

Instead, we think it is likely that CSU leverages AI and improves their products (assuming that they can pass the cost down). Currently, they already have a group of AI specialists exploring this topic.

Risk #6: Culture Erosion

We keep the best for last; culture erosion is the biggest risk as an outsider investing in CSU.

The corporate culture designed by Mark Leonard has been one of tough discipline, yet clever flexibility. Since 2013, every acquisition is subject to the Post Acquisition Review (PAR) scheduled one year after acquisition. This process puts P&L reporting to a standardized template and measures the actual returns against expectations.

If a manager made a wrong assumption, they are not allowed to adjust numbers out to cater for impairment. The error stays in his capital base and permanently lowers the ROIC.

PAR started at headquarters and now has been pushed down to the Operating Group level.

Mark Leonard describes the culture best in his 2017 letter:

Nevertheless, I think all processes should be periodically re-examined for their cost and benefit. An ad-hoc analysis done to understand a problem or opportunity is more likely to translate into action than a quarterly report that gets generated because “we’ve always done it that way”. The former requires curiosity and intelligence, the latter bureaucracy and compliance. If the Operating Groups can learn from their acquisitions by some less burdensome method than PAR, I’m all for it.

As we teach more people at CSU how to deploy capital, we lean on the accumulated data from our historical acquisitions to help maintain investment discipline. We have base rates for a variety of key operating metrics. Whether it is a neophyte investment champion arguing that a particular acquisition is “special”, or a senior executive being tempted by a large acquisition, we have enough data to make the discussion rational, not emotional. We all know whether the key assumptions are being pushed to the 55th or 95th percentiles of our historical distributions.

My only significant concern regarding investment discipline, is that we’ll be tempted to drop our hurdle rates as our cash balances climb.

CSU is also strict about not counting synergies in assessing targets, even for bolt-on acquisitions. They assess each acquisition on a stand-alone basis and don’t cater for synergy benefits, any actual synergies that happen later is treated as a bonus.

Managers have to prove that deals are self sufficient and don’t depend on synergies to pass the hurdle rate.

Of course, in actual business practice they do take advantage of synergies like cross-selling. So the acquired companies actually benefit from entering into the vast ecosystem of CSU, now they have opportunities to expand their product in a related vertical market. However, the investment modelling cannot assume synergies.

Mark Leonard has stepped down as CEO recently due to health concerns and so he will not be involved in the details of complex deals. Mark Miller is the new CEO and has worked with CSU, Volaris Group and its subsidiaries for more than 30 years. Miller co-founded Trapeze Group in 1988, which was the first company acquired by CSU in 1995, it has now expanded on a global scale. He also currently serves on the Boards of:

Lumine Group (telecom-focused independent division)

Modaxo (people transportation division)

ventureLAB (technology incubator)

VoxCell BioInnovation (biotech and tissue engineering company)

Mark Miller has emphasized that CSU will not change the way it operates.