Principles: Pricing Power

Intro

Most people have a definition of pricing power as the ability to raise prices without a decrease in quantity.

However, this simple statement skips over a much richer breakdown of what gives rise to pricing power, situations where it works or fails, and why it’s linked to the value creation process that all businesses strive to maximize.

In a 2010 interview, Warren Buffett said this about pricing power:

The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price 10%, then you’ve got a terrible business.

Notice that he said that the power to raise prices is coupled with not losing business to a competitor.

“Not losing business” is not as simple as keeping quantity sold unchanged when prices are raised.

To help us think about pricing power, there is a paper written in 1996 by Adam Brandenburger and Harborne Stuart titled “Value-based Strategy”.

Value Stick Framework

If there’s one common pattern for all companies attempting to venture into systematic price hikes in the name of pricing power but end up failing, losing market share, and damaging their reputation, it’s this: they all go too close to or cross the customer’s willingness to pay.

And while that may read like an obvious statement, the importance lies in the words “getting too close”.

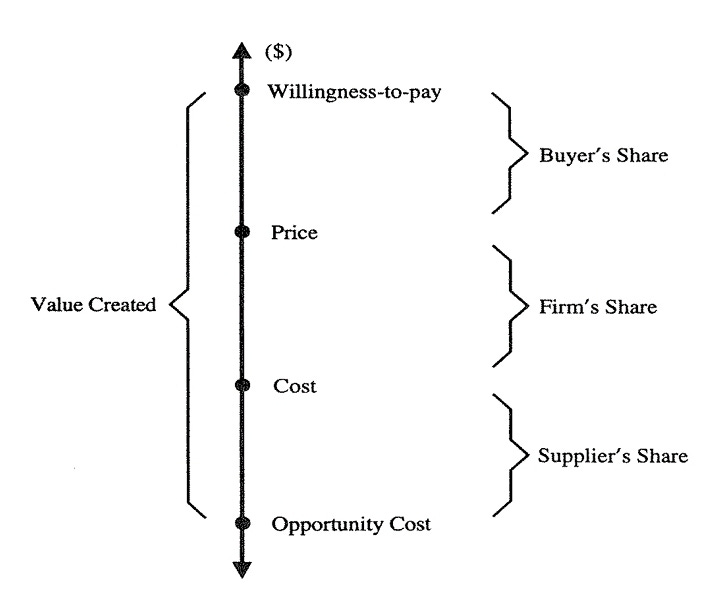

Brandenburger and Stuart presented their simple model of value creation that looked beyond just shareholder value but included buyers and suppliers in the value creation process as well. It looks like this:

Four elements are present in value creation:

Willingness to pay (WTP) is the maximum a customer will pay for a product or service.

Price is what the business charges.

Cost is what the business incurs for providing the product or service.

Opportunity cost, or willingness to sell (WTS), is the minimum amount a supplier (including employees) would accept to provide the product or service.

From this diagram, we can identify these surpluses:

1. Consumer surplus = WTP – Price

2. Supplier surplus = Cost – WTS

3. Value to Firm = Price – Cost

4. Total value created = WTP – WTS

Consumer Surplus

With the above mental model, consider two different companies serving the same market:

Company A prices its product far below WTP, but still above cost.

Company B tries to capture as much value as possible and prices its product just below the customer’s WTP.

Suppose that customers WTP is $10 and both companies incur the same cost of $2.

Now, Company A charges only $6, creating consumer surplus of $4 (WTP – Price). It also creates $4 of value to the firm (Price – Cost).

Company B charges $9, leaving only $1 of consumer surplus, but capturing much more value to the firm of $7.

At first glance, you would think that Company B has better economics, reflected by higher margins and return on assets. This will mean more profits can be reinvested to create even more sales.

But there’s a problem: when Company B gets too close to customer’s WTP, the price elasticity starts to widen, and a marginal increase in prices will cause a disproportionate decrease in demand.

As customers are faced with more options, Company B has to constantly innovate to differentiate its products.

Now you can see that Company B is left with little pricing power as market dynamics would cause customer retention rates to drop alongside lifetime value.

In its efforts to derive as much value as possible in the short term, Company B fails to expand its moat and eventually sees its large reinvestment efforts create subpar returns.

Company A, on the other hand, has signaled to customers that their needs are put ahead of corporate profits. The product provides more value than its price. By leaving consumer surplus on the table, Company A earns intangible reputation and goodwill. Instead of thinking about how to create more sales, it focused more on how to increase WTP through delighting customers.

In keeping the price low relative to value, Company A expands its addressable market by capturing those customers who have a lower WTP than the average group. Eventually, economies of scale bring in additional sales that allow it to maintain the WTP-price ratio.

As WTP increases naturally every year, Company A makes sure to maintain its WTP-price spread by hiking prices steadily at the same rate.

For Company A, the result is a durable compounder as customers are continuously delighted.

As for Company B… it’s game over.

Many analysts think that pricing power is quantitatively measured by gross margin. That is true, even more so when margins are stable, it can be an indicator that a business can charge a lot.

However, you now understand that pricing power also depends on WTP. The current prices a company charges and how much it raises them doesn’t indicate true pricing power. What matters is the distance between WTP and price; we like to term it “latent pricing power”.

Latent pricing power plus the ability to increase customer’s WTP is the reason for a widening moat!

Supplier Surplus

A wide WTP-price spread represents just a snapshot, and while it is the strongest indicator of pricing power, it does not guarantee permanence.

For example, AutoZone has a strong corporate culture grounded in the inspirational mindset that the rational and equitable division of value is the only way of ensuring that its business grows in strength as it grows in size.

But a culture like that is rare. A wide WTP-price spread has no way of ensuring that culture erosion will not occur, giving in to the temptation to harvest more value, especially if pressured by short-term investors and activists.

Since there are two ends to the Value Stick framework, we also need to think about the WTS-cost spread as it plays an equally important role in widening economic moats.

For most companies, their most important supplier is their employees. It might be counter-intuitive that paying employees more, thus increasing cost and creating more supplier surplus, can create long-term shareholder value.

Yet, it works when greater supplier surplus is fitted within a strong culture that promotes intrinsic motivation.

For example, Costco pays its lower-level employees much more than its retail peers, which has led to a 9-year average tenure of its US employees, of which more than 12,000 of them worked at Costco for more than 25 years. This loyalty is unheard of in retail!

Jim Sinegal was notoriously frugal when it came to spending at headquarters and on C-suite pay. Instead, he directed all of the savings into paying average store-level workers good hourly wages. Sinegal perfectly understood the value of a dedicated worker, which leads to superior customer service, higher sales, and lifelong club members.

On a similar note, Buffett in 1998 described this effect on See’s Candy:

If you are See’s Candy, you want to do everything in the world to make sure that the experience basically of giving that gift leads to a favorable reaction. It means what is in the box, it means the person who sells it to you, because all of our business is done when we are terribly busy.

People come in during those weeks before Chirstmas, Valentine’s Day, and there are long lines. So at five o’clock in the afternoon some woman is selling someone the last box candy and that person has been waiting in line for maybe 20 or 30 customers. And if the salesperson smiles at that last customer, our moat has widened and if she snarls at them, our moat has narrowed.

We can’t see it, but it is going on everyday. But it is the key… the total part of product delivery. It is having the association between See’s Candy and happiness. That is what business is all about.

Lengthen The Value Stick

So far, we know that the indicators of true pricing power lie in the maximization of both consumer and supplier surpluses.

Yet, this mode of thinking is static, while businesses are fluid ecosystems.

Early in a company’s growth trajectory, it makes sense to reward customers and suppliers disproportionately since referrals and retention are essential to the development of a valuable franchise. As a business matures, the value division can be changed.

The more important key is to figure out what a business does to lengthen both sides of the Value Stick. For durable pricing power, any changes to the division of value should be made for purely competitive reasons and not driven by short-term profit taking.

Focusing on what a company does right to create more value for customers and suppliers is what helps us get to the core of its moat.

Ways to Increase WTP

There are mainly 3 ways to increase WTP.

Love

“Love” is a fitting word to describe the phenomenon where customers are not only genuinely happy with a product/service, but also root for the company’s success.

Most people would think that brand power is the solution, but love goes beyond brand because a well-known brand does not always create durable value.

Think about some of the largest car brands or airlines; everyone knows their brand names, but how many have delivered good returns and possess pricing power?

A well-loved brand is what increases WTP. The WTP for a brand is high if you are in the habit of using it, have an emotional connection, trust or believe that it confers social status.

Loving customers cheer on the businesses that make their favourite products. They advertise for free and tie their personality to these products.

Technological edges can be lost, and scale economies can be matched, but a loved brand name often endures.

Too many factors go into developing the loving customer, but it can be summarized as providing high-quality and low variance outcomes. If an outcome doesn’t disappoint customers, then over time, it builds trust. Raising the WTP bar is all about accumulating more trust.

The most common way to build trust is by reducing search costs. The less thinking a customer has to do before making a purchase, the more it leans on trust, and the lower their acquisition cost.

If they are delighted, then their trust is validated, and their love is deepened. A good example is Coca-Cola reducing search costs via distribution scale; they have built global distribution networks that ensure their products are everywhere and its taste has zero variance; Coke tastes as it should be. It is a well-loved brand, and people will continue to drink Coke consistently even if prices grow slightly above inflation. This signals an increasing WTP.

Other wildly successful examples are ultra luxury brands like Hermes. They produce a small number of high-quality products, although supply is limited, but it doesn’t carry a high search cost. Because customers don’t research on what luxury bag to buy, they simply go into a Hermes store and leave with a feeling of prestige and exclusivity.

Utility

Increasing the WTP for a customer through utility requires that the product becomes increasingly useful to the customer.

For example, BEES (B2B e-commerce platform) that Anheuser-Busch has developed over 7 years acts as a platform to share the enormous amounts of data gathered about consumer preferences across its markets.

This data helps their customers (restaurant/bar owners) estimate demand in different categories and indicate price elasticity across the labels. They can utilize BEES to keep track of their inventory and sales progression to determine when and where demand spikes for a particular label. By helping their customers succeed, the relationship strengthens, and the WTP increases.

A product that’s well-integrated into the customer’s workflow without straining expenses is another way of expanding WTP through utility.

Microsoft is a fantastic example; with their mission-critical productivity software, cloud services and operating system, the utility delivered to individuals and businesses all over the world is immense.

Network Effect

This factor is widely known, especially for two-sided networks where more buyers attract more sellers and the flywheel reinforces itself. Customers in a network will have a higher WTP because products/services are endorsed by a large community.

It also increases the utility for customers when a large group of suppliers is consolidated on a platform. These quality of life features can justify a higher WTP.

Ways to Expand WTS

What companies frequently overlook is the option to create more value and thus increase their pricing power by expanding their supplier’s WTS. When a company can lower its own cost by improving the supplier’s WTS, the situation goes from zero-sum to win-win.

Data

One way of reducing WTS is through data. Today, most businesses collect a lot of transactional data. Sharing this information with the supplier can lower their WTS.

Suppose a supplier currently earns a NOPAT margin of 10% and has a capital turnover of 1.5x, so ROIC = 10% * 1.5 = 15%. Let’s say we give the supplier transactional data to more accurately predict inventory levels, which helps reduce their invested capital, increasing capital turnover to 2.5x.

Now, the supplier could reduce prices to achieve the same 15% ROIC. NOPAT margin can shrink to 6%, offset by higher capital turnover of 2.5x.

In fact, the supplier can lower the price just slightly to NOPAT margin 8% and get a higher ROIC of 20%, creating value for both parties.

Costco does this with their suppliers, and they can negotiate for lower prices and expands the WTS because of their strategy of low SKUs. When the number of items managed is low, Costco can spend time with detailed analysis with suppliers and manage relationships more tightly than their peers. Furthermore, the reputation that Costco always transfers cost savings into lower prices for customers means that Costco is actually negotiating on behalf of customers and not totally to enrich corporate profits. This can explain why their suppliers see Costco as a source of reliable revenues, and thus expands the WTS.

Scale

Another obvious way to expand WTS is through economies of scale. Size brings along bargaining power, for example, Autozone has negative working capital as they collect payments from customers upfront while having favorable (non-predatory) payment terms with suppliers.

Economically, this translates to suppliers financing Autozone’s growth.

Suppliers are willing to expand their WTS in order to do business with companies that operate on a large scale.

Lessons

Pricing power is one of the sole reasons for durable value creation, and when you find a company that possesses it in the true sense of the term, it’s about sitting tight and letting the intrinsic value come slowly over time.

The Value Stick framework is useful to think about pricing power in terms of value, not price or costs.

The lesson is this: businesses that have pricing power in its most durable form are usually the ones that are under-earning by design. This opens up extraordinary long-term investment opportunities for those who are willing to look beyond reported earnings.