CSU.TO: Constellation Software (1)

Recap

We have written about a study note on CSU when the company was trading at ~$50b just 2 months back (Nov 2025). Please read it to get an understanding of the business model, economics and the recent narratives on AI threat.

In our previous note, we didn’t buy CSU because we thought it was not cheap yet. Between these 2 months, nothing fundamental has changed, except that CSU stock price fell -23%, market cap is $41b now. The enterprise value (EV) is also $41b, net of cash and debt with recourse to CSU.

This price is cheap enough now and so we bought our first tranche at C$2,666.

Let’s jump straight into some valuation scenarios.

Valuation

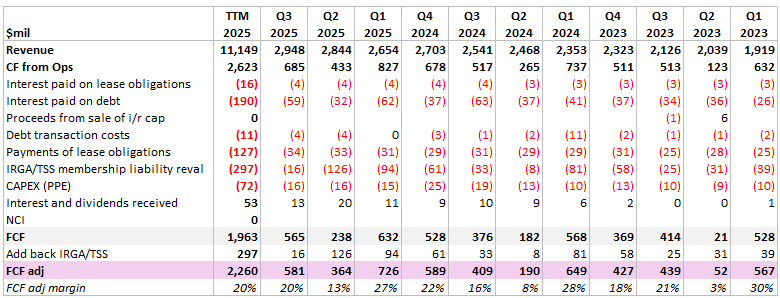

First we need to know what’s the free cashflow (FCF) attributable to shareholders. We take the way CSU calculates it, but add back IRGA/TSS non-cash charges:

This IRGA/TSS revaluation non-cash charge is due to Joday Group who acquired 33.29% of the voting rights of Topicus (TSS), a subsidiary of CSU and the indirect 100% owner of TSS at time of acquisition. Total proceeds from this transaction was €39m ($49m). Due to CSU 100% retention of TSS free cashflow and the agreement being recognized under IFRS accounting, CSU recorded the “cost” of including TSS free cashflow that belongs to Joday. The changes in valuation of IRGA/TSS is primarily due to TSS maintenance revenues and changes in net tangible assets. Due to the liability denominated in Euros, we get some FX effects when translating to US$.

We are adding back IRGA/TSS revaluation because it’s just an accounting thing that doesn’t reduce the FCF to shareholders.

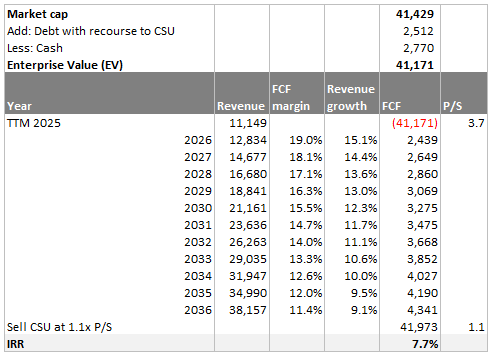

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Now, at enterprise value (EV) of $41.2b, we are paying a price-to-sales (P/S) of 3.7x. We can simulate a 10-year disaster scenario for CSU by shrinking both revenue growth and FCF margins. We can then find the IRR for this stream of cash, assuming we sell CSU at 1.1x P/S for $42b at the end of 10 years, almost the same EV as today:

These are our assumptions:

Start FCF margins equal to the average of past decade at 19%. Reduce proportionally every year by -5%.

Start revenue growth equal to TTM at +15%. Reduce proportionally every year by -5%.

Sell the investment at 1.1x sales at the end of 10 years.

IRR turns out to be ~8%. Not too bad for a pessimistic scenario.

Reverse DCF

We can back-solve for what kind of growth profile is implicit in the market cap today through reverse DCF.

This horrible scenario solves for it:

FCF growth starts at +10% (about half of historical 6 year CAGR of 24%). Reduce growth by -1% each year and terminal decline of -3.5% (implied exit FCF multiple = 6.3x).

Discount rate = 12.5%.

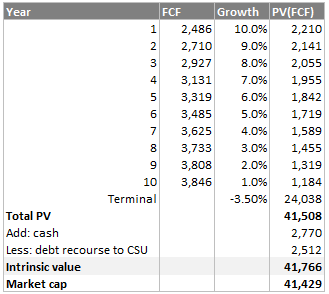

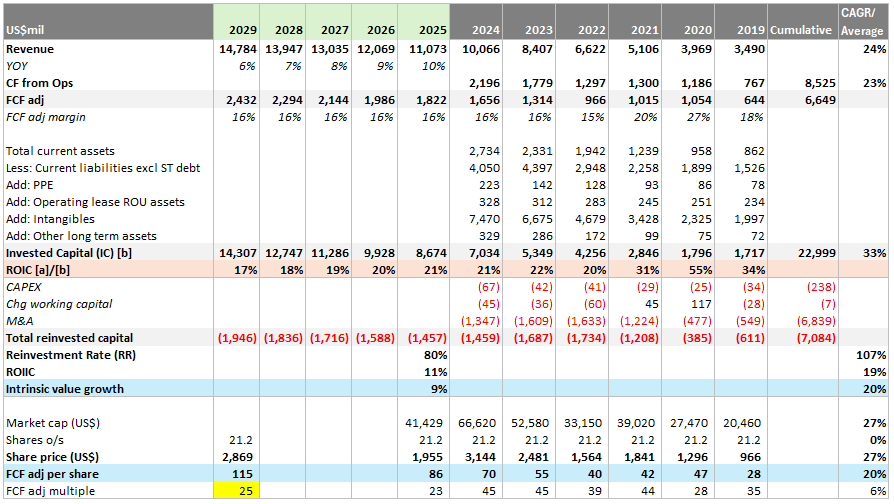

ROIC & FCF Multiples

Firstly, we show that intrinsic value growth, calculated by multiplying Reinvestment Rate (RR) and Return on Incremental Invested Capital (ROIIC), explains FCF/share growth. Add on FCF multiple expansion and we can explain why share price grew at +27% since 2019.

Note: FCF numbers are different from the study note because we adjust out IRGA/TSS non-cash charges.

As we can see, CSU is very CAPEX-light, this is logical as VMS software have strong recurring revenues without much need for reinvestment. So almost all of the cash is spent on M&A. Cumulatively, total reinvested capital was $7.1b while FCF was $6.6b, so the RR was 107%.

The 19% ROIIC is just the incremental FCF divided by incremental invested capital between 2019 and 2024.

If you agree that business value growth is determined by how much capital was reinvested and at what return, then multiply these 2 numbers and you get +20% intrinsic value growth.

The sanity check is against the FCF/share CAGR of +20%, add on +6% CAGR multiple expansion and we explain for share price CAGR of +27%.

With this framework, let’s project outwards. These are our assumptions from 2025 to 2029:

Revenue growth to slow down from +10% to +6%.

FCF margins stable at 16%.

ROIC decrease from 21% to 17% reflecting larger size M&A.

RR decrease to 80% reflecting lesser M&A opportunities.

This setup results in ROIIC 11%, intrinsic value growth +9%.

If shares count is unchanged, FCF/share would be $115.

If we want +10% CAGR from $1,955/share today, the exit multiple is 25x (slightly higher than current 23x).

Yield + Growth

Lastly, we can simply solve for the required growth given the starting FCF yield.

r = E/P + g

where, r = returns

E/P = earnings yield

g = long run growth rate

TTM FCF yield is ~5% now. To get +10% returns, CSU has to compound on average +5% over the long run. Suppose +2.5% comes from pricing inflation, then we just need +2.5% from somewhere else.

That's not a high hurdle to achieve, provided that we think CSU business is not going to zero any time soon.

Conclusion

We think the stock is priced for quite a pessimistic outcome. Investors can speculate about the scenarios where the business is totally impaired, but there’s no rational or thoughtful reason why CSU business will disappear in the foreseeable future.

One imaginative argument is that AI (or some other tech) becomes so advanced that customers can do their own VMS software. This type of thinking is not unfamiliar when it comes to technological change; a similar argument has been made before for Copart and AutoZone.

When accident prevention tech came on, people thought that the declining accident frequency would reduce the relevance of Copart business. The accident rate did indeed fall, but the cost of those technologies also made repairing cars more expensive such that a modest hit would cause the modern car to be totaled. As a result, total loss frequency went on a monotonic increase for decades.

For AutoZone, technology also made more durable car parts; in the past copper spark plugs lasted only 20k+ miles, now iridium plugs last 100k+ miles! The business has always faced declining unit volumes, but it didn’t become irrelevant because the price per unit increased dramatically.

This is what we are trying to say: Events in investing are nuanced, they rarely turn a business on/off in an instant.

CSU is a people business. Companies can use tech to increase sales productivity, but the selling will always be people driven. Because trust and relationships are important. The M&A employees have relationships with a database of ~70,000 business leads globally, cultivating relationships for years, sharing best practices and developing software catered specifically for their customers. Obviously, the benefits of AI is also available to CSU, we should argue that it’s actually CSU that cascades these benefits down to their customers and extract even more economic value out of the business model.

In fact, during the acquisition process CSU typically require the managers to take an earn-out period of 3–4 years. But actually most of them stay on, and ~70% of seniors managers at CSU are people who sold their business to CSU in the past.

The result is a breeding ground and deep bench of VMS experts, each of them are experts in their own vertical markets. We would bet that the power new technology in the hands of these human experts is a net benefit to CSU. That’s the reason why CSU has been so effective in buying hundreds of companies and improving their profitability.

Lastly, the attractiveness of VMS is the small market size, because of that it can only support one or two players. The success of CSU has never been barriers of entry. It is easy to create a competing software in VMS but what problem does it solve for the end user who already on tailor-made software for years?

The fact that AI makes it easier to make software does nothing for the end user. Because VMS costs are a tiny % of revenues while being mission critical. A competitor could lower the initial selling price but the bulk of cost is actually coming from maintenance & support. This category makes up the largest revenue pie for CSU.

By entering into VMS, most of the time a competitor is trying to steal customers, and it’s very hard to do that to customers who use a mission critical product.

Public markets will always supply prices that are irrational, we as investors have to supply the patience and equanimity.

The astronomical concept of constellations has evolved from ancient navigation tools into modern organizational metaphors with profound implications for technological architecture. What strikes me most about constellation-based thinking is how it mirrors distributed systems theory - individual nodes working independently yet coordinating to create emergent functionality greater than their sum. From spacecraft networks to software architecture, the constellation model represents a fundamental shift from monolithic to distributed paradigms. The historical precedent of celestial navigation demonstrates humanity's innate ability to recognize patterns and extract meaning from apparent chaos. In contemporary business contexts, constellation structures enable both specialization and integration simultaneously, a duality that traditional hierarchical models struggle to achieve.

Thoughts?