Study: Constellation Software

Recent Events

For readers who are already familiar with Constellation Software (CSU), we address the recent concern that AI is disrupting VMS.

CSU stock is down -34% from peak, representing the largest stock drawdown in almost 20 years. While attributing any stock movement to a single variable is fraught with imprecision, there is no doubt that investors are worried that AI will mean more competition and thus customer losses for CSU.

Value is never gained during good times, and we take the opposing view that the market is mistaken by backward causation, because CSU’s moat never stemmed from the lack of competition in the first place.

As we know, the total addressable markets (TAM) for vertical market software (VMS) can be very small, usually just around $5m. The reason why competition for a niche vertical doesn’t exist, isn’t because of costs or barriers to entry. It’s because the market cannot support more than one player and once a customer is adequately served, there is no incentive to switch.

Even before AI, a single software engineer could produce a competing product. There is nothing particularly complex about most of these VMS, they are often clunky with very rudimentary UI.

The reason why this software engineer wouldn’t find success is because creating a similar product doesn’t solve any customer problems. The customer is already happy with the existing software.

Furthermore, VMS is mission critical but makes up only a small fraction of total expenses. So even if a competitor charges less, it doesn’t make a difference to the customer. There are many challenges in pulling out an existing solution, reintegrating with adjacent systems, retraining employees, and risking failure from the new software.

Why would the customer care to do all of this for the same product that cost a little less?

In fact, CSU collects service revenues for setting up and customizing the software for the customer. So, they already have the exact software they need and want. If AI allows software to be made easier, then they still are going to have to hire someone to use AI on their behalf to create that software. It still doesn’t get rid of the issue that using AI to create new software doesn’t solve anything for them. Also, there’s no barriers to stop CSU from using AI to build those functions cheaply.

The idea that now there is more potential competition misses the fact that great companies don’t win because competition is lacking. They win because they have solved a customer’s problem better than anything else.

History

Founder Mark Leonard is a private and enigmatic character. Look at his picture, he looks like Gandalf:

Leonard enjoyed his youth, taking 7 good years to finish college and then went to get his MBA from the University of Ontario. After graduating he worked in the venture capital (VC) industry for 11 years.

Then in 1995, Leonard raised CAD25m mostly from the pension fund Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System and some VC investors to start CSU.

During his VC days, he noticed the excessive penchant for TAM, and anything that would not be able to serve a large market or disrupt a large incumbent almost could not get access to VC funding.

Leonard thought there are a lot of companies out there which are fundamentally good businesses, and at the right price, investing in such businesses could give good returns. One area of the market he felt was consistently underserved and yet had a very attractive business economics was Vertical Market Software (VMS).

Although CSU went public in Canada in 2006, it did not raise any money; they only became public to create liquidity for the VC investors who sold at the then $70m valuation.

What is VMS?

VMS is customized and industry specific/niche software solutions that have all the typical attractive properties of Horizontal Market Software (HMS) except the TAM. HMS products such as Microsoft Office have demand from almost every industry whereas VMS companies have a very limited market size.

There are many VMS businesses around the world, think about the submarkets within industries like transportation, healthcare, payments, education etc. The niche TAM is not small in aggregate. While there are differences based on end-market and customer types, those different VMS markets have quite homogeneous targets.

This homogeneity is key to develop some standardization and best practices in the M&A process, which CSU needs in order to push M&A down the organization and scale deal volumes.

The average VMS company benefits from some unique economic advantages. They have very strong unit economics due to their mission critical software, while also being a small fraction of total operating costs. This gives rise to predictable recurring revenues and pricing power.

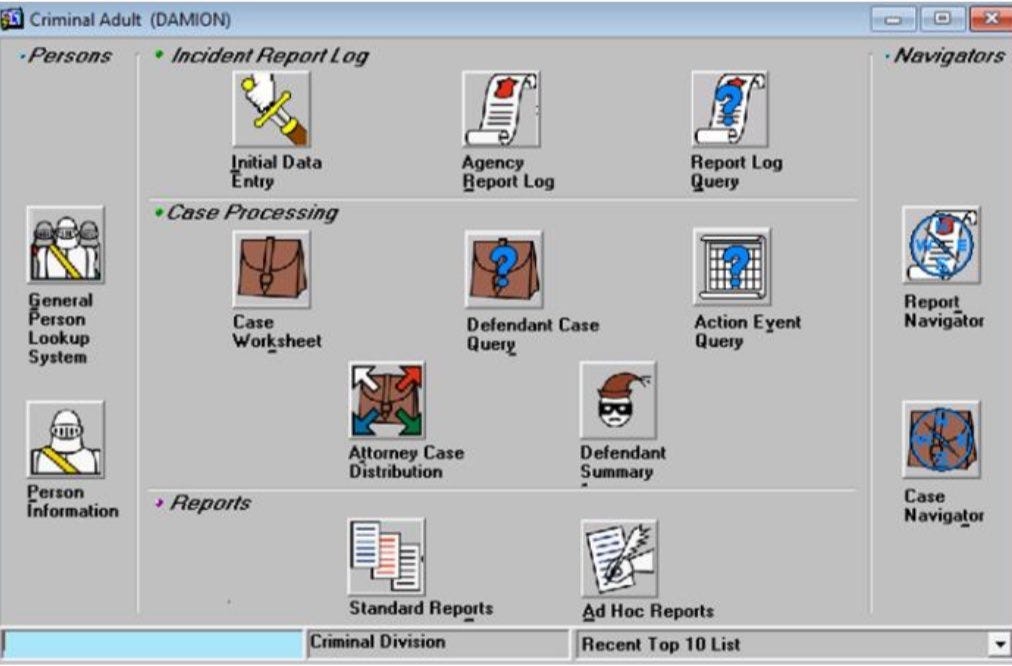

VMS is also capital-light. HMS faces the threat of commoditization, requiring them to spend money on R&D for the best user experience and features. However, VMS doesn’t have to do that, it just has to be dependable. Look at one of CSU products, built in 1996 for the Seattle Justice System, it looks antiquated and it is, but it is still in use today:

Once a VMS is integrated into a system, it stays there like infrastructure and there’s very little incentives for customers to switch unless there’s a total breakdown.

The cashflow dynamics is also attractive. Customers pay recurring fees upfront annually while the service is delivered. Cashflow conversion against net income is therefore high.

Most of these small VMS companies are just owners operating in corporate form, they have low customer diversification compared to HMS where size provides resilience through diversity.

This is why CSU can pay a low multiples for a VMS with predictable cashflows. This reduces the risk of buying a wrong company and the small deal size means that CSU just has to be right on average, making it easier to push M&A down the organization.

Organization Structure

Today, CSU is a perpetual owner of several hundreds of VMS companies across the world spanning over 75 verticals which range from golf course software to marina management, and diagramming tools for crash scenes to police departments.

CSU consists of 6 Operating Groups (OG) housing hundreds of Business Units (BU) under them. Each BU can hold many individual VMS companies:

Acquisition Process

The board and/or headquarters (HQ) recommends and sets hurdle rates for acquisition.

HQ creates a threshold for acquisition for OGs for which they won’t be required to ask for approval. Similarly, the OGs can have similar threshold for BU managers. The M&A team calculates potential IRR for the deal and creates scenarios for each acquisition to see where their base case scenario fall in distribution based on historical acquisition track record.

One year after the acquisition, there is Post Acquisition Review (PAR) in which the team discusses the initial projections and actual result as well as the lessons from the experience.

BUs try to use cash to acquire more companies and if they don’t see much opportunity, they can repatriate cash to HQ.

But if a BU consistently generates high IRR, HQ may ask the BU to “Keep Your Capital” (KYC, introduced in 2018) so that BUs are more incentivized for deploying capital at lower IRR but still higher than hurdle rates. On the other hand, if an acquisition does poorly, it remains in their capital base when calculating the ROIC. Managers cannot adjust their capital base for impairments which acts as an incentive to allocate capital prudently.

Sourcing a potential deal and maintaining relationship with the founder/CEO of a target typically takes 5 years. The rationale behind this grooming is when the founder is prepared to sell, CSU should be the first company they think about. Because of these interactions, CSU managers have a much better grasp on their verticals and when they come across a deal, they can come with a price usually much quicker than other parties. This is what we meant by VMS targets are quite homogeneous.

CSU tries to avoid bidding games when buying companies. There is nothing stopping a price sensitive target to ask for higher prices from another acquirer. That’s why these types of targets don’t get in; CSU is a home for founders who care about their business more than exit price and want a permanent stay. Other private equity acquirers most likely sell these companies after restructuring them.

Economies of Decentralization

For the acquisition process described above to work, decentralization is very important. This shows up in CSU decision to not seek economies of scale:

Shareholders sometimes ask why we don’t pursue economies of scale by centralising functions such as Research & Development and Sales & Marketing. My personal preference is to instead focus on keeping our business units small, and the majority of the decision making down at the business unit level.

Partly this is a function of my experience with small high performance teams when I was a venture capitalist, and partly it is a function of seeing that most vertical markets have several viable competitors who exhibit little correlation between their profitability and relative scale.

Some of our Operating Group GM’s agree with me, while others are less convinced.

There are a number of implications if you share my view: We should

a) regularly divide our largest business units into smaller, more focused business units unless there is an overwhelmingly obvious reason to keep them whole,

b) operate the majority of the businesses that we acquire as separate units rather than merge them with existing CSU businesses, and

c) drive down cost at the head office and Operating Group level.

Shareholders letters, 2014

Most business models that depend on capital allocation allow autonomy at operating level, but centralize capital allocation decisions. Instead, CSU seeks economies of decentralization, pushing allocation decisions down the organization. Compared to Berkshire, this way of thinking in CSU is necessary because their portfolio of software businesses are not capital intensive, they will run into a problem of cash drag if acquisitions are confined to HQ only.

During the first decade that Mark Leonard managed CSU, he was largely responsible for making all of the acquisition decisions. In 2006, when CSU had 30 BUs, he delegated most of this task to the OG managers. Large acquisitions were still vetted by HQ, but most small capital allocation decisions became decentralized.

Over the next decade, OGs built and trained their own M&A staff, and further delegated some responsibility down to Portfolio Managers (of which there might be 5-10 at each OG).

By 2016, there were 26 OG managers and Portfolio Managers that spent more than 50% of their time on M&A, and another 60 full-time M&A professionals spread across CSU.

In 2018, CSU gave OG managers the autonomy to approve acquisitions up to $20m, pushing more of the capital deployment responsibility down the chain.

This culture of decentralization resulted in M&A employees who once managed a VMS business. They cultivated deep relationships with targets, knowing their competitors and understanding their products. These are the people who are best fit for curating a wish-list for acquisition targets.

These M&A people don’t work at HQ, instead they are deep in the specific VMS that they are familiar with. In fact, the test for decentralization is to see how many people are at HQ versus total employees. There are about 20 people at HQ and 64,000 employees working for CSU.

As CSU grows by adding more BUs and verticals, more M&A staff inevitably follow, which helps make decentralized M&A scalable. Over the decades, CSU has completed hundreds of acquisitions and has collected a lot of proprietary data to help them in projecting quantitatively on which IRR percentile a new acquisition will likely land.

Without the scalable deal funnel, proprietary data sets, quantitative framework for allocating capital, and the education process, it is unlikely that CSU would have been successful at decentralizing M&A. We see no compelling reason that CSU couldn’t continue leveraging this advantage.

IRR Obsession

As CSU market cap grows it inevitably becomes harder to move the needle when acquisition size is small. Many shareholders have encouraged Mark Leonard to consider larger acquisitions, even if that requires to drop the IRR hurdle rate a little.

Leonard doesn’t buy this idea and he explained his rationale in his 2015 letter:

We analysed the weighted average expected IRR’s for each of our acquisitions by year from 1995 to early 2015 and compared them with the prevailing hurdle rate we were using when the acquisitions were made. During that twenty year period we made three changes to the hurdle rate, one up, two down.

The weighted average expected IRR for each vintage (eg. all of the acquisitions done in 2004) of acquisitions tended to drop or increase to the newly implemented hurdle rate. Said another way, when we dropped our hurdle rate, it dragged down the expected IRR for all the opportunities that we subsequently pursued, not just those at the margin.

We try to capture this idea by saying “hurdle rates are magnetic”. It now takes a very brave soul to propose a hurdle rate drop at CSU.

Now, we know that IRR is time sensitive and can produce some results that not everyone will agree with. For example, a declining business can produce good IRR if purchased at a cheap price.

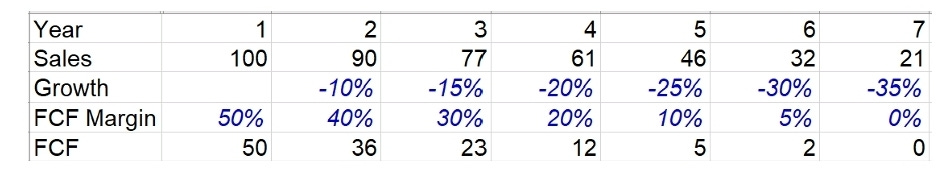

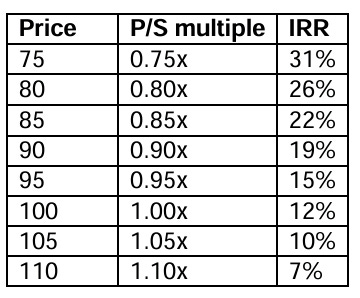

Consider a business that shrinks over time and eventually produces zero free cashflow (FCF):

Intuitively, you might think that this is a bad investment. However, your IRR depends on what price paid:

You can still achieve a high IRR if the price paid is cheap.

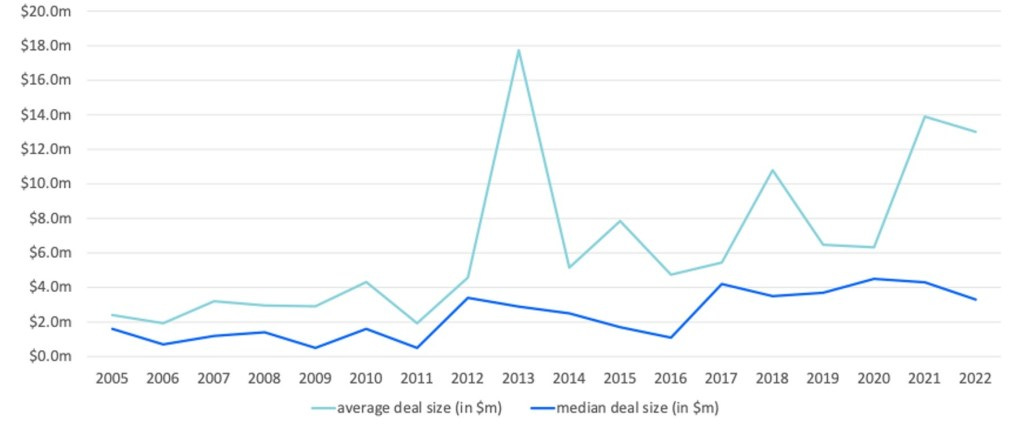

On average, CSU pays around 1x P/S, and the average company is certainly not a shrinking one like our example above. Therefore, it’s safe to assume that CSU is achieving high IRR for its acquisitions.

In the 2015 shareholders letter, Mark Leonard further expounds on this IRR obsession:

We have tracked the IRR for all of the acquisitions that we’ve made since 2004 (ie. >95% of the acquisition capital that we’ve deployed). When we graph the IRR’s vs the post-acquisition Organic Growth (OGr) of each investment, there is little correlation. If you are really striving to see a relationship, you might argue that our best and our worst IRR are both associated with low post-acquisition organic growth.

Based on the data, there are much more obvious drivers of IRR than OGr. For instance, revenue multiple paid (lower purchase price multiples are better – no revelation there), and post-acquisition EBITA margin (fatter margin acquisitions tend to generate better IRR – somewhat intuitive, but needs further work).

How about a thought experiment? Assume attractive return opportunities are scarce and that you are an excellent forecaster. For the same price you can purchase a high profit declining revenue business or a lower profit growing business, both of which you forecast to generate the same attractive after tax IRR. Which would you rather buy?

It’s easy to go down the pro and con rabbit hole of the false dichotomy.

The answer we’ve settled on (though the debate still rages), is that you make both kinds of investments. The scarcity of attractive return opportunities trumps all other criteria.

We care about IRR, irrespective of whether it is associated with high or low organic growth.

In recent years, CSU has been willing to pursue larger sized deals, ROIC will probably decrease as a result. For example, they bought Allscripts Healthcare Solutions in 2022 for $700m ($670m upfront + $30m earned out). Purchase price was 0.9x sales and 8x FCF.

Competition & Runway

VC firms hunt for unicorns. By design, they are not interested in mature software businesses with small TAM, and therefore don’t compete directly with CSU in M&A.

Private equity (PE) competes with CSU. But fortunately, most large PE firms are run by generalists who lack the experience in VMS. Neither are they stable homes for founder-led VMS businesses who appreciate autonomy and legacy more than price.

On the other end, small tech-focused PE firms might not have the scope, resources, access to talent, or reputation of CSU.

The sweet spot is a small corner of the universe like ESW Capital, not too big or small. CSU estimates that there might only be a dozen or so PE firms like this in the US who they consider to be meaningful competitors.

Some corporates have a similar M&A strategy and can compete with CSU. Roper Technologies is an example, but the overlap is probably not great. There are very few corporates like Roper, and many of them are dedicated to only a handful of verticals and/or are too big to be considered serious competitors.

People often talk about external competitors but at CSU internal competition becomes an advantage.

The CSU database has 200,000 leads globally between the divisions of Volaris, Vela, Harris, Perseus, Jonas and Topicus. There cannot be inter-OG poaching unless there has been no contact for 12 months. That stops OG from bidding each other up and it also stops complacency. If a business development leads are constantly poached, it means the manager was not doing a good enough job. It’s a way of incentivizing everybody to track how many they lost to another CSU group.

Internal competition is at the heart of CSU culture. That is an effective system for business development people who are effectively salesmen.

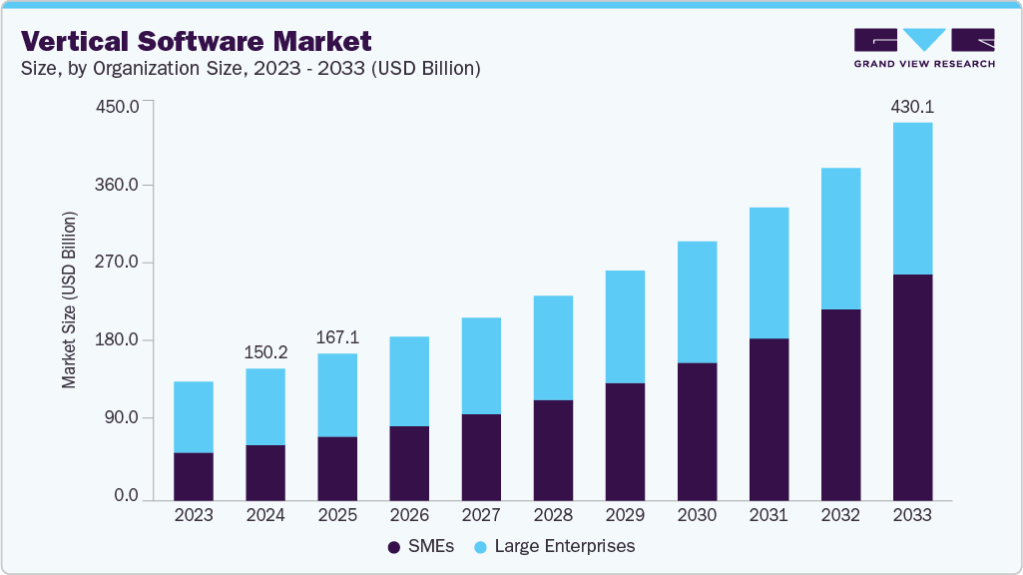

There are some global estimates on VMS that suggest the runway is quite healthy:

The VMS market is large and fragmented, although CSU has some competitive advantages that allow them to execute on lots of deals and achieve above average IRR, but it is definitely getting more difficult to keep the machine running at full speed. Operating cashflow (CFO) has grown exponentially over time. Pre-2015, CSU had no problem deploying most of that cash on M&A. Post-2015, CSU consistently spent less than 100% of CFO on M&A, and cash balances grew significantly. They ended up paying a large special dividend in 2019, because they just couldn’t find enough acquisitions that exceeded internal hurdle rates for new investments.

Monitoring Post-acquisition

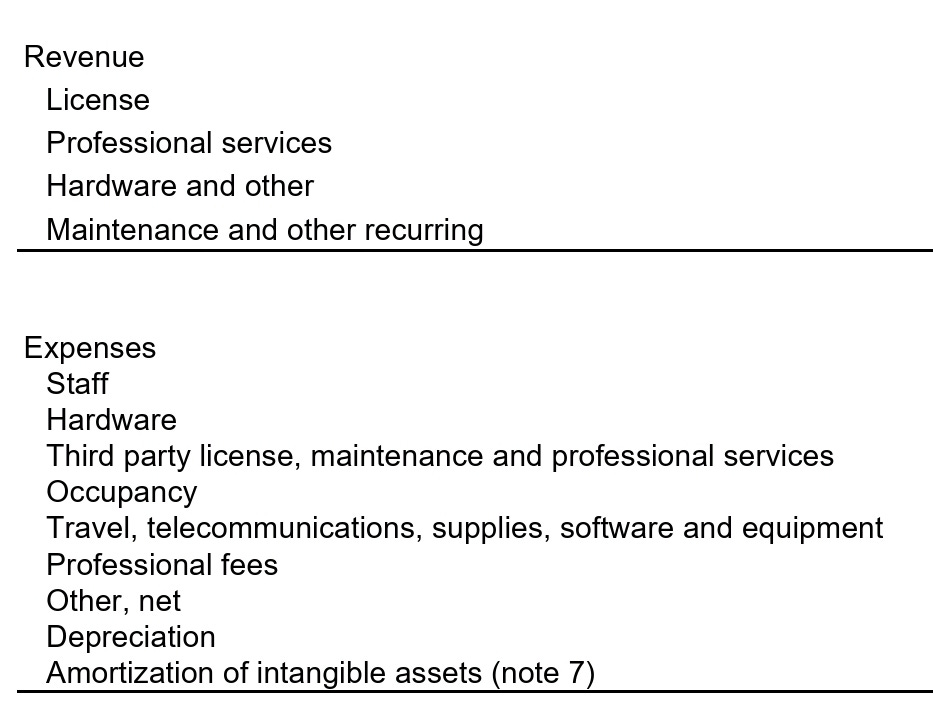

When a company makes it into CSU, they have to align financial reporting into CSU format.

Everything is viewed under the same lens.

Attrition is measured most closely. Most businesses view attrition as customers lost, but customers you keep who pay less is also attrition. CSU attrition metric doesn’t include up sell or new customers; they are only interested in the combination of lost and down sell customers.

If the combination of those two is less than 5%, then that business has a good chance of growing. Even in a bad year, not much can go wrong. That feeds back into business quality and what they should pay based on the future.

Incentives & Ownership

The long-term focus is accomplished by mandating that at least 25% of the incentive compensation for the majority of our senior employees who earn in excess of $75,000 per annum and have bonuses in excess of $10,000 per annum be reinvested in shares of CSU that are subject to restrictions on resale for a period of three to ten years.

At a minimum, these restrictions require employees to hold 100% of their shares for the first 2 years following acquisition, and then 1/3 of such shares may be sold in each of years three, four and five.

Senior executives are required to invest 75% of their bonus in shares of CSU that are subject to the same restrictions on resale for a period of 10 years.

Once every 5 years, employees may elect to receive 100% of their bonus in cash.

2025 proxy, pg.15

CSU makes their senior executives buy shares at market prices, so they have not issued a single share based compensation.

That also means when CSU stock price keeps rising (which it historically has) the senior managers are incentivized to drive performance.

As at 2024, executives and directors collectively own 1.3 million (6.16%) of CSU outstanding shares, this has increased from 5.6% in 2021 (there were no shares repurchases, diluted shares since 2007 has remained unchanged at 21.19 million).

The new CEO, Mark Miller, owns 251,680 shares worth CAD852m. Miller has worked with Volaris Group and its subsidiaries for more than 30 years. He co-founded Trapeze Group in 1988, which was the first company acquired by CSU in 1995.

Mark Leonard abruptly stepped down as CEO but remains as Chairman due to health concerns. He owns 407,797 shares.

ROIC, ROIIC, Reinvestment Rate

When we look at the performance of CSU, it is clear that intrinsic value growth is driven by returns of incremental invested capital (ROIIC) and reinvestment rate (RR).

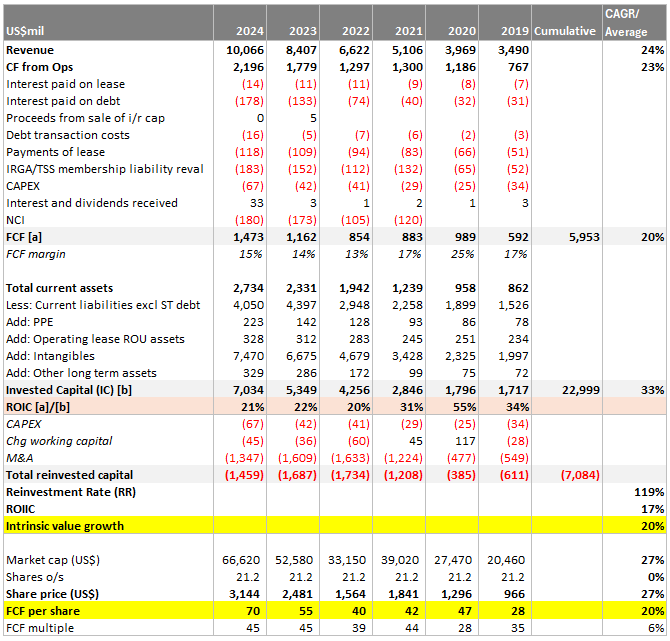

Expectedly, since 2019 when CSU started to explore larger deal sizes, the ROIC started to fall. We can also see CSU is really capital-light with less than 1% revenues spent on CAPEX. The main use of cash is for M&A.

Put together, for the last 6 years the ROIIC is 17% and RR is 119%, producing intrinsic value CAGR of 20%. This aligns with FCF per share CAGR of 20%, the remaining 6% came from FCF multiple expansion, adding up to ~27% share price CAGR.

Currently, the FCF multiple contracted back to 30x (TTM FCF $1.7b, market cap $51b).

We don’t think multiples are reliable to predict the future, because CSU could fetch a lower multiple depending on the expected future returns on larger M&A deals. So the important question is are we able to guess what is the future RR and ROIIC?

If the following scenario happens in the next 5 years, the intrinsic value growth will be ~12%:

RR drops to 80% due to size constraints.

ROIC drops from 21% to 17% due to larger deals size.

Revenue grows at 24% per year.

FCF margin 15%.

Of course, if CSU continues to produce historical returns then we think the multiples should re-rate higher.

Conclusion

After such a long post, these ideas are actually already well known by the market. We are giving no special insight.

The idea that CSU will continue to sustain the M&A engine depends alot on corporate culture. We think Mark Leonard would have left the operations of CSU in good hands.

Investors of CSU would have to trust internal benchmarks are held to high standards and incentive structure remains rational.

We also feel that CSU has to reinvent itself beyond VMS because size will eventually compress ROIC. Acquiring small businesses cannot continue much longer when CSU market cap is more than $50b.